Master's Thesis

Psychological Needs and Motivations of Older Adults in Video Games

The growth of the gaming industry has led to fascinating research into player motivations, yet very little has been done to explore those of older adults. This thesis aimed to fill this gap by investigating the preferences and motivations of this demographic. One of the two studies yielded statistically significant findings that hope to provide guidance for more inclusive game design.

tl;dr

MEng Design Engineering Master's thesis

Academic research, data analysis, accessibility

Adobe Creative Cloud, Microsoft Office

Introduction

Audrey Buchanan was 88 when she made headlines for her impressive play time of more than 3,500 hours in Animal Crossing: New Leaf. Her story surprised (and endeared) many, yet research shows that almost 50% of Americans aged 50+ play video games regularly.

Despite the statistics, older adults are often underrepresented in academic research related to play. This prevents the creation of games that address their needs and preferences to promote healthy engagement.

This is a summary of an academic study rooted in psychological theory and statistical analysis. I have tried to make it accessible to a general audience, but some familiarity may be helpful.

The plural “we” signifies this thesis was supervised by a senior researcher, however all experiments and data analysis were conducted by me.

Study aims

This thesis had four main objectives:

- Define the tastes of older adults, and compare them to those of younger players.

- Identify older adults’ general opinion on video games.

- Produce insights for video game developers to promote inclusive design.

- Encourage older adults to embrace a new form of entertainment.

Background

After conducting a review of the existing literature, we found that most research focused on younger audiences and did not account for demographic differences. However, there have been fascinating studies on the motivations for video game play in general, as well as the cognitive benefits of regular play.

If you’re interested in the psychological theories and studies that served as a foundation to this thesis, you can read it in full here.

Methodology

We formulated two hypotheses that we would test through two separate studies.

- Older adults may have a negative perception of video games, which prevents them from playing.

- Older adults’ tastes differ from younger audiences, and they would prefer nonviolent over violent video games.

Study 1: A survey-based approach to hypothesis 1

Participants

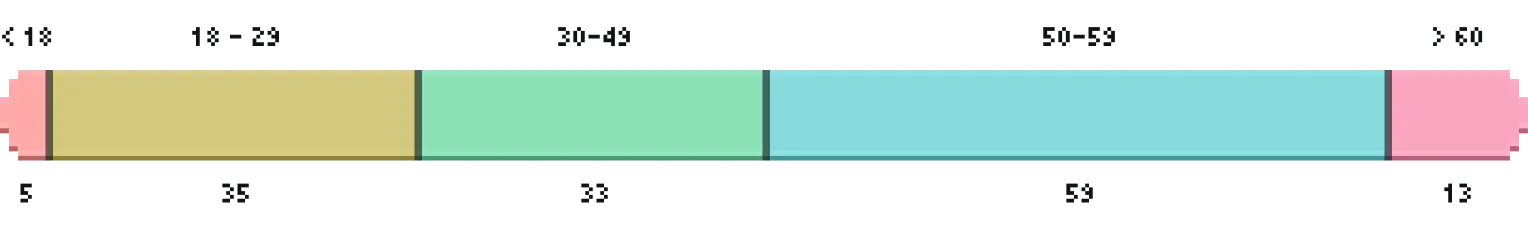

The survey was distributed through personal contacts and online gaming communities. We obtained 145 responses, with 50% of respondents aged 50+.

Method

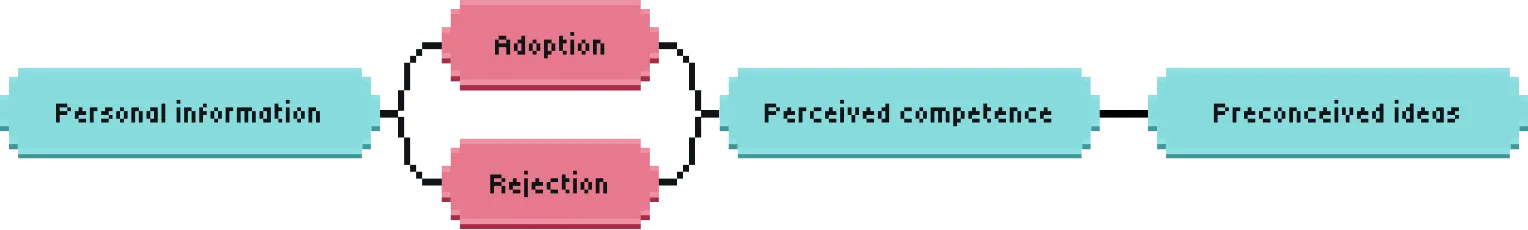

Our first hypothesis was tested through an anonymous Qualtrics survey, with questions exploring:

- Reasons for adoption

- Reasons for rejection

- Perceived competence

- Negative/positive perception

- Effects of age, gender, and frequency of play

To allow us to investigate reasons for adoption as well as rejection, paths diverged based on the answer to the question “do you play video games?”.

Results

We first tested for the effects of age and gender in adoption rates. They both had major effects, with people aged 50 and over reporting lower frequency of play and female participants reporting lower adoption rates.

In terms of perceived competence, older adults reported significantly lower competence. Interestingly, this was more pronounced in regular players.

Older adults reported lower adoption and perceived competence. This was more pronounced in female participants.

To test our hypothesis regarding preconceptions, we tested for effects between age and frequency of play on perception of video games. We found that older adults are more likely to perceive video games as too violent. Perhaps not surprisingly, frequency of play had a bigger effect, with regular players perceiving video games as less violent, less isolating, and more popular than non-players.

The findings partially supported our hypothesis and provided a second interesting insight.

Holding a negative or positive perception is more tightly related to frequency of play, rather than age.

There were no statistically significant findings related to reasons for adoption or rejection, but we found some interesting trends. For example, adults aged 50-69 were likely to think that there are no options for them in the market.

Study 2: An experimental approach to hypothesis 2

Participants

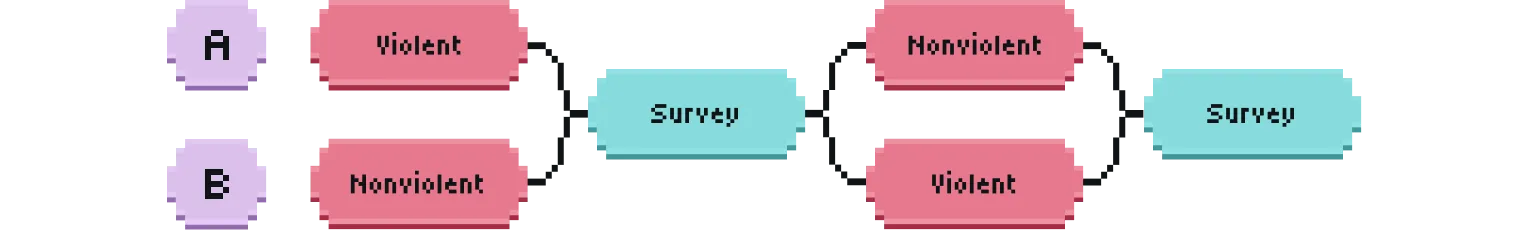

The participants for the second study were selected to have varying levels of familiarity with video games. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the sample size was limited. We worked with 5 young adults aged 18-29 and 5 older adults aged 50-69.

Method

To test our second hypothesis, we ran a simple crossover study via moderated video call sessions.

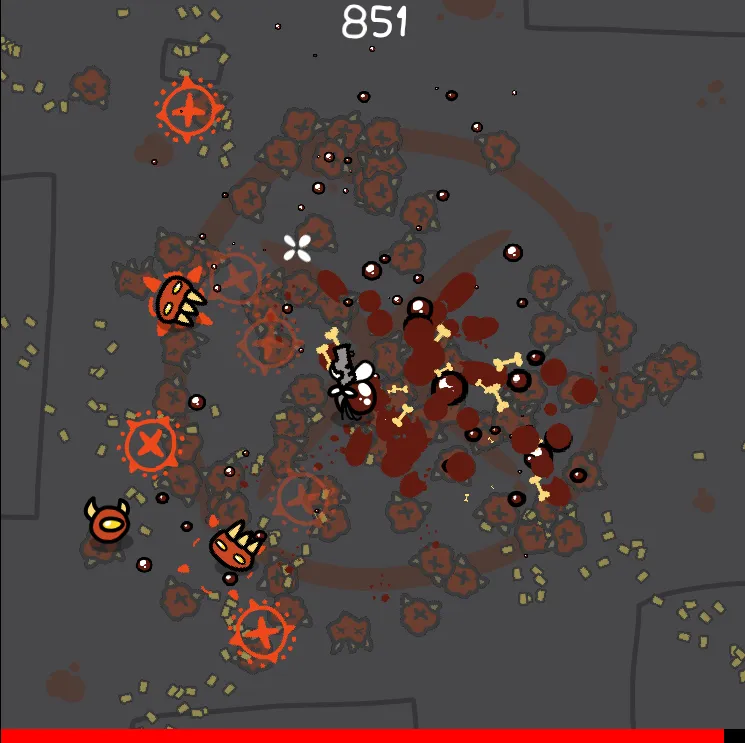

First, we selected two free-to-play games that were easily accessible to participants. One game was nonviolent (Sushi Roll, a simple clicker game developed by Famobi), and the other was violent (Hell Sucker, a top-down 2D shooter developed by CheeseBaron2).

Participants were randomly assigned the first game they’d play. Each participant played each game for 10 minutes while being observed, then filled out a short questionnaire based on pre-existing measures, before switching to the second game.

Results

The small sample size prevented us from obtaining statistically significant findings. However, we identified some trends worth mentioning.

Feelings of competence decreased with Hell Sucker, with participants expressing frustration towards the controls and interface. Feelings of autonomy were also lower.

Preference scores stayed consistent across both games for players under 50, but older adults expressed higher preference for Sushi Roll.

Takeaways

One of our aims was to provide developers with suggestions for more inclusive game design. These are some of the trends we identified that could provide some insight into the design of games aimed at an older demographic.

Perceived competence was confirmed to decrease with age, and it is also tied to prior experience. Providing difficulty settings accounts for player differences and makes games accessible to a much wider audience.

Our second study highlights the impact of complex controls in both competence and preference. They can be a high barrier of entry, especially for older adults with less dexterity or muscle memory. Simple and intuitive controls are recommended, preferably with customisation options such as button remapping.

I was personally saddened to hear older adults express that video games are not made for them, despite the many different options that exist nowadays. This highlights the need for more diverse game narratives that represent a wide range of players, or a collective effort in bringing such games into the spotlight.

Of course, these are only a few of many accessibility considerations that should be taken into account. If you’d like to learn more, I recommend checking out the Game Accessibility Guidelines.

Conclusion

Since I defended my thesis, accessibility has become a bigger focus. Within the past few years, including extensive accessibility settings has become a reason for praise within the industry, and prizes are awarded to studios that go above and beyond. However, there is still a long way to go.

Accessibility is not only beneficial to older players, or those with disabilities. It improves the experience for everyone, and should not be up for debate.